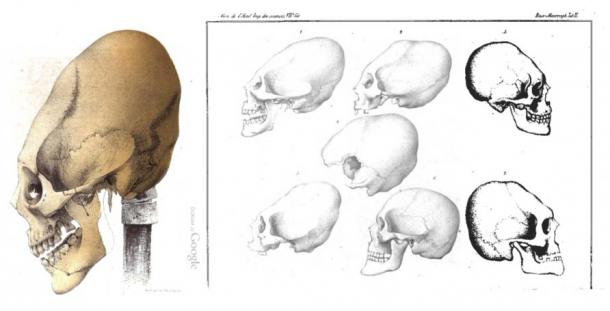

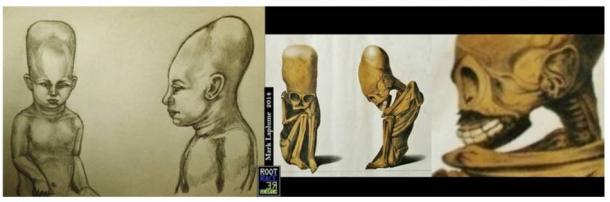

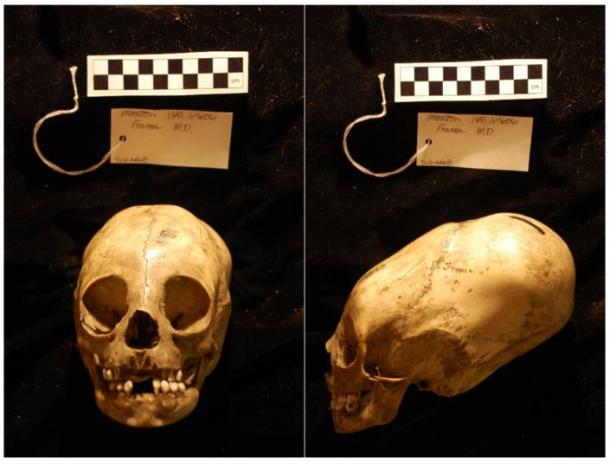

Una reveladora comparación entre cabezas alargadas naturalmente y cabezas alargadas artificialmente. La forma de los cráneos alargados naturalmente es bastante sencilla en comparación con el contorno restringido de los cráneos que han sufrido una deformación craneal al nacer.

Otras características de las cabezas naturalmente alargadas son la masa y el volumen que superan los cráneos humanos normales en al menos un 50 por ciento. La deformación craneal artificial sólo modifica la forma, mientras que las características craneales siguen siendo las mismas. Aquellos con cabezas alargadas artificialmente lo han hecho para imitar a aquellos antepasados que eran tenidos en alta estima. Recuerda que la imitación es la mayor forma de adulación.

Los cráneos alargados suelen explicarse en términos de vendas de cabeza o deformaciones craneales artificiales. Este paradigma surgió en la primera mitad del siglo XIX como una forma de explicar los cráneos inusuales descubiertos en Europa y América del Sur, en lugares como Crimea y Perú respectivamente. La idea principal detrás del paradigma de vendar la cabeza es que TODOS los cráneos alargados son el resultado de una modificación intencional de la forma del cráneo mediante la aplicación de presión externa. En otras palabras, TODOS los cráneos alargados son simplemente cráneos “normales” deformados, similares a los de los humanos modernos.

Cráneo alargado de Crimea y otras partes del mundo, Baer 1860

Desafiando el paradigma

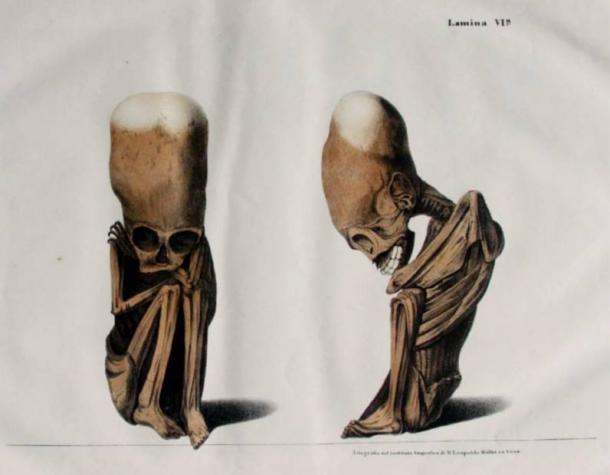

¿Qué evidencia podría desafiar este paradigma? Derecha: la existencia de fetos con cráneos alargados, es decir, evidencia de que dichos cráneos ya tenían una forma alargada en el útero , antes de que fuera posible vendarles la cabeza. ¿Tenemos tal evidencia? ¡Sí! Además, ¡la comunidad académica conoce esta evidencia desde hace más de 163 años!

Rivero y Tschudi en Antigüedades Peruanas (1851 español, 1853 inglés) sostienen que los protagonistas de la hipótesis de la deformación craneal artificial se equivocan, pues sólo habían considerado cráneos de adultos. En otras palabras, la hipótesis no tiene en cuenta los cráneos de los bebés y, lo más importante, los fetos que tenían una forma de cráneo alargada similar.

- La historia de los cráneos alargados y la historia negada de los pueblos antiguos: una entrevista con Mark Laplume

- ¿Qué fue de los cabezas de cono?

Vale la pena citar a Rivero y Tschudi:

“Nosotros mismos hemos observado el mismo hecho [de ausencia de signos de presión artificial – IG] en muchas momias de niños de tierna edad, que, aunque llevaban ropa, todavía no presentaban ningún vestigio o apariencia de presión en el cráneo. . Más aún: la misma formación de la cabeza se presenta en niños aún no nacidos; y de esta verdad hemos tenido prueba convincente en la vista de un feto, encerrado en el vientre de una momia de mujer embarazada, que encontramos en una cueva de Huichay, a dos leguas de Tarma, y que se encuentra, en este momento, en nuestra colección [mi énfasis – IG].

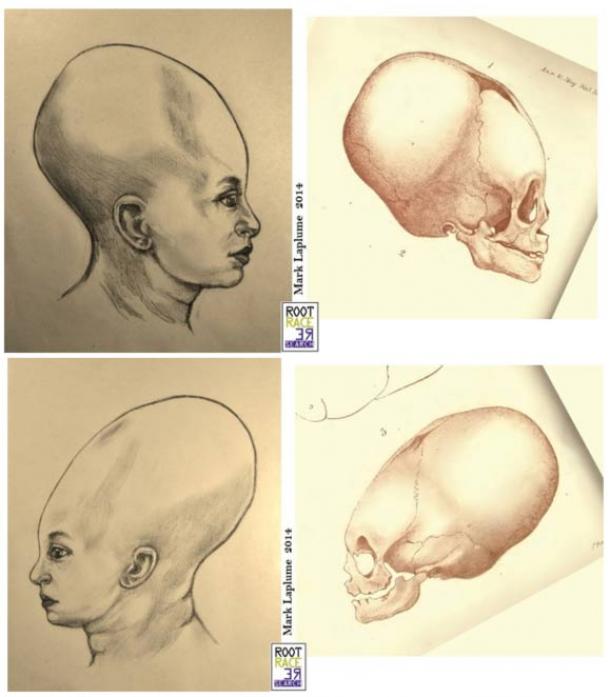

Litografía de D. Leopoldo Mueller de la edición española de 1851 de Antigüedades Peruanas

El profesor D’Outrepont, de gran celebridad en el departamento de obstetricia, nos ha asegurado que el feto tiene siete meses de edad. Pertenece, según una formación del cráneo muy claramente definida, a la tribu de los Huancas. Presentamos al lector un dibujo de esta prueba concluyente e interesante en oposición a los defensores de la acción mecánica como causa única y exclusiva de la forma frenológica [es decir, craneal – sin connotación negativa en ese momento – IG] de la raza peruana.

La misma prueba se encuentra en otra momia que existe en el museo de Lima, bajo la dirección de Don ME de Rivero.

La reconstrucción de Mark Laplume del feto de Rivero y Tschudi

Los cráneos alargados de los bebés

Los investigadores europeos disponían de cráneos alargados de niños ya en 1838. Los cráneos de los “antiguos peruanos” también estaban en la colección de Samuel Morton en Filadelfia.

Two elongated infant skulls, which Rivero and Tschudi mention in Peruvian Antiquities were discovered and brought to England by Captain Blankley and presented to the Museum of the Devon and Cornwall Natural History Society in 1838. Dr. Bellamy provided a detailed description of these skulls in 1842, suggesting that they belonged to two infants – male and female, few months and about a year old respectively. He indicated substantial structural differences from those of “normal” infant skulls and the absence of the signs of artificial pressure, as well as their similarity to other “Titicacan” skulls in the Museum of the College of Surgeons in London.

Lithographs of the skulls by J. Basire from Bellamy’s article (1842) and Mark Laplume’s artistic reconstructions

The evidence of elongated skulls present in fetuses and 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥ren had lead Rivero and Tschudi, Bellamy, Graves and others to a hypothesis that these skulls belonged to an extinct race of people, who left their legacy on the populations who succeeded them as a practice of artificial cranial deformation. I discuss this hypothesis in more detail in The Looming Collapse Of The Artificial Cranial Deformation Paradigm . Part 1. Un/Born With Elongated Head and Part 2. Naturally Elongated .

The question now is how it happened that the cranial deformation paradigm became so prevalent? The answer to a large extent consists in the authority of Morton’s expert opinion and his extensive collection of skulls, which is now located in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology . His influence was significant enough at the time to close the debate on elongated skulls for the next century and a half; until independent researchers, and I would like to mention Robert Connolly (who popularized elongated skulls in mid 1990s) and Brien Foerster, in particular, started to raise questions about the validity of the cranial deformation hypothesis by locating and showing elongated skulls to the public interested in finding out the true story of human origins.

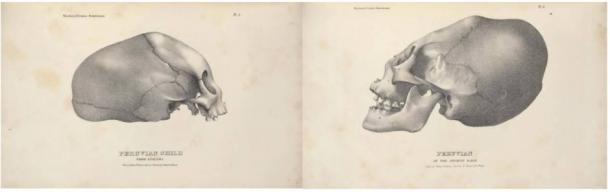

Lithographs by John Collins, 1839 from Samuel Morton’s ‘Crania Americana’

Cranial Features of Ancient Peruvians

In Crania Americana Morton offered a description of peculiar elongated skulls which differed from the elongated skulls produced by various artificial means. He suggested that the territory of Peru and Bolivia was previously inhabited by the race of “Ancient Peruvians”.

“I have been so fortunate as to have the examination, in my own and other collections, of nearly one hundred Peruvian crania: and the result is, that Peru appears to have been at different times peopled by two nations of differently formed crania, one of which is perhaps extinct, or at least exists only as blended by adventitious circumstances, in various remote and scattered tribes of the present Indian race. Of these two families, that which was antecedent to the appearance of the Incas is designated as the Ancient Peruvian, of which the remains have hitherto been found only in Peru, and especially in that division of it now called Bolivia.”

Although Ancient Peruvians had naturally elongated skulls, Morton concluded that they further tried to articulate this feature by head binding. This is an interesting observation in itself, since it raises a question why a race with naturally elongated skulls would aspire to further elongate them. Perhaps they were also preceded by a race whose skulls were even more elongated?

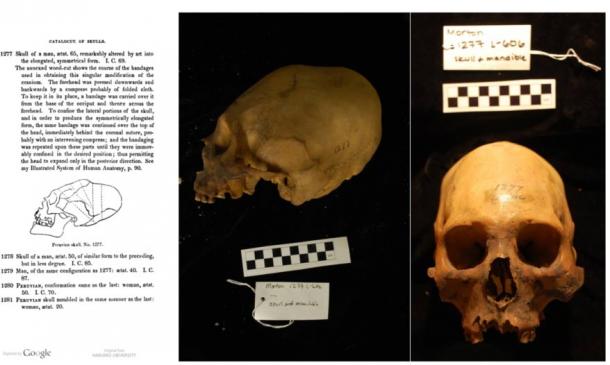

Morton Collection, Skull #1277, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the Open Research Scan Archive at Penn, and Janet Monge and P. Thomas Schoenemann; image in front from Meigs, 1857

Subsequently, Morton changed his opinion and started to consider all elongated skulls as an exclusive result of head-binding. However, in light of Rivero and Tschudi’s fetuses with elongated skulls, as well as hundreds of infant and 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥ren elongated skulls which are now available to researchers, it is necessary to open the debate about “Ancient Peruvians” and their counterparts (see my interview with Mark Laplume) in other part of the world.

Accordingly, it is necessary to revisit Morton’s original encounter with elongated skulls. This is how he originally described cranial features of Ancient Peruvians:

“[The head] is small, greatly elongated, narrow its whole length, with a very retreating forehead, and possessing more symmetry than is usual in skulls of the American race. The face projects, the upper jaw is thrust forward , and the teeth are inclined outward. The orbits of the eyes are large and rounded, the nasal bones salient, the zygomatic arches expanded; and there is a remarkable simplicity in the sutures that connect the bones of the cranium.”

Morton Collection, Skull #1681, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the Open Research Scan Archive at Penn, and Janet Monge and P. Thomas Schoenemann

Dado que hay al menos dos momias que contienen fetos con cráneos alargados, además de cientos de bebés y niños con cráneos alargados (ver Niños de los ‘cráneos alargados’ como un desafío a la teoría de la ‘deformación craneal artificial’ y RootRaceResearch), un La tarea prioritaria para la comunidad académica sería identificar la ubicación física de las momias y proceder al análisis de ADN, que actualmente lo realizan investigadores independientes y entusiastas que carecen de recursos infraestructurales y financieros y enfrentan importantes obstáculos para obtener los permisos necesarios. Cabe señalar que se trata de ADN muy antiguo, cuyo análisis es un procedimiento complejo y costoso.