Funchal, Portugal. The waiter in the small cafe used to be a soldier. A long time ago, Alberto Martins enlisted in the army with his peer Dinis Aveiro, who later had a son named Cristiano Ronaldo.

They have known each other since 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥hood, when they flew to Africa together on September 4, 1974. They had to sit on the wooden benches of a rickety train going through Angola. The train was so slow that they were able to jump out and smoke a few cigarettes before giving chase and jumping back. The vans waited at the last train station and took them to a village near the Zambia border called Mossuma.

There is their new home, in the hot desert of Africa, with its unforgiving night, evoking a sense of familiarity to boys who grew up on an island surrounded by deep, fast-flowing waters. .

They returned to the island after the war and went nowhere. Aveiro got an odd job, and there he drank a lot. Relying on the generosity of friends, he always turned to alcohol whenever he had money. Before Ronaldo became famous, Aveiro was so pathetic that he had to sell his son’s shirt at Man Utd to earn money to buy alcohol.

He always told his friends, including Martins, that his son wanted to take everything he could not achieve in life. “My son wants to be the best player in the world,” he told them, and they always laughed at him.

“We called him an idiot.” Martins said. “But he always believed in it.”

Stories about superstars are often built on father-son stories, right? One always tries to drive the story in such a way that one becomes great by trying to be worthy of someone, or by trying to live well when that person is dead. But that’s certainly true here.

In a recent documentary about himself, Ronaldo shows his loneliness and psychological insecurity quite clearly. In the first shot, we see Ronaldo in the house, he’s having breakfast with his son. The only point that brings a feeling of sadness in the frame is the portrait of an unnamed man behind the father and son.

That is Ronaldo’s late father.

We know that Aveiro had to fight a senseless war as a young man, like most other eligible boys during the military dictatorship in Portugal, he was sent to Angola (the colony of Portugal) to counter the indigenous freedom struggles. He is not on the winning side. And when he returned, he changed completely, as the movie says. Aveiro drinks to death and creates a strained relationship with his son. Although he never hit his son, he often assaulted Ronaldo’s mother. When Aveiro’s liver broke, Ronaldo chartered a private plane to take him to England for emergency, but it was too late.

Despite everything, Ronaldo still holds the past as the son of a defeated soldier. Boys like that often grow up trying to be something important. Perhaps even now, Ronaldo still wants to prove something, to show his father what kind of person he has become. There is only one official document that shows Ronaldo’s feelings, and that is the movie, because he rarely accepts interviews. Ronaldo’s agent turned down ESPN, and his family wanted money in exchange for the statements.

Aveiro continues to appear at the end of Ronaldo’s film, in the old house, where he sees his son still a boy. And then the movie switches to today’s Ronaldo, who is showing off his perfect abs and famous smile. In his bright glory, Ronaldo still wishes that his father could see him now.

Advertisements

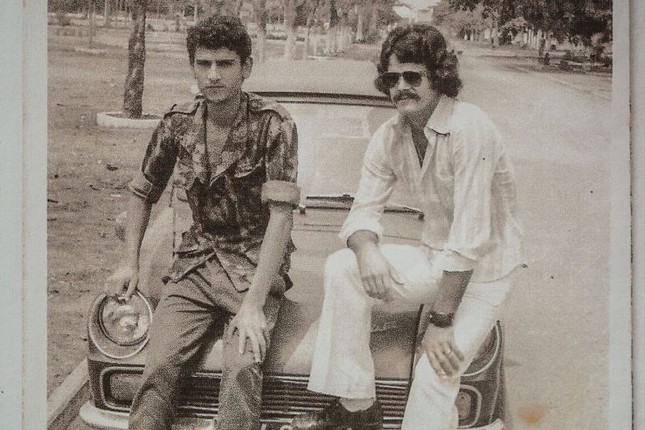

Aveiro family (photo: ronaldo7.net)

As the movie shows, Ronaldo never really understood his father. There are still many veterans on the island in Madeira. They think of Aveiro whenever they see his son on television, with a feeling of both pride and sadness. They watched Portugal draw 1-1 with Iceland in their Euro 2016 opener and they have answers to questions Ronaldo never thought of.

Ronaldo’s father was taken out of the war after it was over, for the sole reason of being alive. During their training, a group of young officers grow weary of being sent to war they have no hope of winning, overthrowing the dictatorship and creating a new democratic government. When the dictatorship collapsed on April 25, 1974, the war was essentially over.

AdvertisementPROMOTED CONTENTLàm sạch mạch máu và loại bỏ chứng tăng huyết áp đến giàMore …28574249 Viêm da cơ địa rất khó hết, đọc ngay bí mật này!More …28574249

Viêm da cơ địa rất khó hết, đọc ngay bí mật này!More …28574249 Lý do viêm da cơ địa luôn tái lại. Xem ngay cách giải quyếtMore …28574249

Lý do viêm da cơ địa luôn tái lại. Xem ngay cách giải quyếtMore …28574249

Two friends Aveiro (left) and Martins in Africa

When the 4910th battalion stepped out of the plane and into another war five months later, everyone on both sides of the front knew that the Portuguese army had lost. The soldiers from Madeira were the last reinforcement, they came only to smooth the process of handing over the colony to the rebel forces. The train took them to Luso, and the trucks took them to the battalion headquarters. There, they were further subdivided into different garrisons, tasked with supporting the food trucks.

The stories that tell of the mentally destructive events that Aveiro witnessed are not true. A copy of the unit’s files indicates that only 3 of the 500 men died, and not at all because of the enemy. One fell ill, another was in an accident, the other got into a fight with a local ally and was shot dead. “It’s not a real war anymore.” Martins recounted. “So we are not prepared for a war either. Honestly, I don’t think anyone in our battalion fired a bullet at anyone.”

For most soldiers, the worst is living conditions. Many people have malaria, lie in bed, have fever, shiver with cold, and for 3 weeks can’t walk normally. The food rotted before it arrived because of the long route to western Angola.

“We were starving,” said Jose Manuel Coelho, who was on the second team. “There are meals where we only have one piece of bread.”

The soldiers there did not have any amenities, except for a gas-powered refrigerator. And therein lies their most precious thing: cold beer. They live with beer. “The weather is very hot and the water is always hot, it can’t quench your thirst.” Coelho continued. “Beer is our good friend. They have Angola beer: Cuca. Fresh water is pulled from the river into a reservoir, but it has no effect. We don’t drink water. We drink beer instead. We say water can cause many problems, and it should only be used for bathing, cooking, etc. To drink, it must be beer. Now every time I drink beer, I think of Angola.”

People think that Aveiro’s 3rd team is the worst team, when they have to close the peg alone, with no other units to support. But the truth is that many people like it. Their camp was a barracks that stretched along the bank of a great river, with a metal roof and nearby villages. They can have beards if they want.

“It’s so good”. “We didn’t have to do anything,” Martins said. We had food. If we need more meat, we can go hunting. No one bothers us. We can cook beef stew and sometimes, give some to the locals. We played football, played cards, sang songs and even smoked. I gained weight. At that time we just ate and slept, didn’t have to do anything.”

It was a photo of Martins and Aveiro standing side by side, leaning against a car in an African town as they waited to get home. Martins looks quite stylish with long curly hair and a mustache, while Ronaldo’s father wears a military shirt, looking rather awkward and uncomfortable. His friends didn’t want to blame his family situation, or try to find any excuses for his alcohol abuse when he returned home, but they said there were problems in his marriage. grandfather.

An interesting thing happened to Aveiro in Africa, when his car and some other soldiers got stuck in the swamp. Three people slept in the car while the others sought help. The howls appeared in the darkness of the steppe and they never felt alone. They huddled together and smoked cigarettes until the sun came out again.

On October 8, 1975 – 13 months later, a ship named Niassa returned the whole battalion to the coast of Madeira. When they discovered land, some people lost their patience, jumped off the ship and swam home.

Aveiro returns to a country that just fell apart. Over the course of a decade, when military dictatorships spent all their money on wars, national budgets slowly disappeared. According to Martins, this was the reason for the destruction of Aveiro, not the war in Angola, as he struggled to rebuild his life after returning.

In a number of different ways, particularly when speaking to Martins, Aveiro expressed nostalgia for Africa. Life there is very simple: go hunting when hungry, sleep when tired. In Madeira, Aveiro had to look for work.

At a restaurant where Martins worked as a waiter, he talked about his old friend Aveiro.

“There are no jobs available.” Coelho said. “We were left behind. Veterans have no money and are unemployed. Of course when I look at Ronaldo, I think of his father. He had a lot of problems and had nothing to eat, so he turned to alcohol. Friends will buy him wine to drink. He has no money. He’s not eating properly.”

A local football club became Aveiro’s home while he ran errands, managing apparel, drinking at a small bar. It was clearly not a father who could make his son feel proud to look at. From an early age, Ronaldo recognized the way others saw his father.

The above club is where Ronaldo’s career began, before he moved to Sporting Lisbon alone at the age of 12 to try to do something about himself. He only had himself then. When Ronaldo talks about his father at the moment, he admits he is addicted to alcohol and violence, but he blames the war in Angola for his loss. But no one knows if that’s true, or just how Ronaldo made his reputation and polished himself.

Aveiro has lost contact with many of his military friends.

“I haven’t seen him for a long time,” said Antonio Luis, who was part of the first team. “Then I saw Aveiro in the city center when his son had gone to England to play. We sat at coffee and talked all about football. He’s very proud of the boy.”

Less than 2 years later, in September 2005, Aveiro passed away.

He died in London, aged 52, to his own bad reputation and the care of his famous son. Ronaldo did everything he could to save his father.

Death covered the British press. Fans and experts were surprised when Ronaldo suddenly disappeared from a match.

Martins did not attend the funeral. Many people attended, including senior officials and representatives of Man Utd, but Martins did not go. He felt it was no place for old soldiers. Most people come for Ronaldo, not for the dead man who lived in his son’s shadow.

People love Ronaldo so much, but only mention Dinis Aveiro for one day.

More than a week ago it was a chicken day at the Madeira branch of Liga dos Combatentes. This is a holiday equivalent to Veterans Day in the US. Here, the men together enjoy the food and drink each cup of wine. This club is located in an old weapons building that was built centuries ago. Inside the building, a chapel was built to commemorate the soldiers who died in battle, and a small wine bar. From here, soldiers could zoom out into the red-roofed houses, sloping down into the deep green hills that lay by the sea. They were all proud of that indescribably beautiful scenery.

Inside the building, retired Lieutenant Colonel Bernardino Laureano was furious when foreigners suddenly asked him about a soldier with a very famous son. All the soldiers who came out of the war, all the 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥ren who have returned to their motherland, Portugal, which has been severely damaged by the war, deserves help and recognition.

For a moment, it seemed that Laureano wanted to rush in and win enough with the others. He wants to pass a message to Ronaldo, maybe this millionaire player may be willing to help those who have the same fate as his father. “The door will be open if he wants to,” Laureano said. “He can contact us, we would be honored and proud to host Ronaldo here. He is sure to find close friends in Liga, and even those who once knew his father. We have known him for a long time and will never forget him – the way we remember so many names who have had a difficult life.”