Cast your mind back 20 years, which at the moment in golf might seem like 200, and imagine Phil Mickelson in April 2004.

Hall of Fame bound with 22 PGA Tour victories at the prime age of 33. A long, loose left-handed swing whose daring could be justified by the game’s ultimate mistake eraser, the Phil Phlop, as majestic and singular as Kareem’s Sky Hook. A showman who won the crowd with a shy grin his father, Phil Sr., called “the mark of a really fine human being.” A buoyant competitor who unleashed a performative arrogance in practice-round money games, filling the space between audacious shots with know-it-all monologues that entertained while establishing alpha-dog cred.

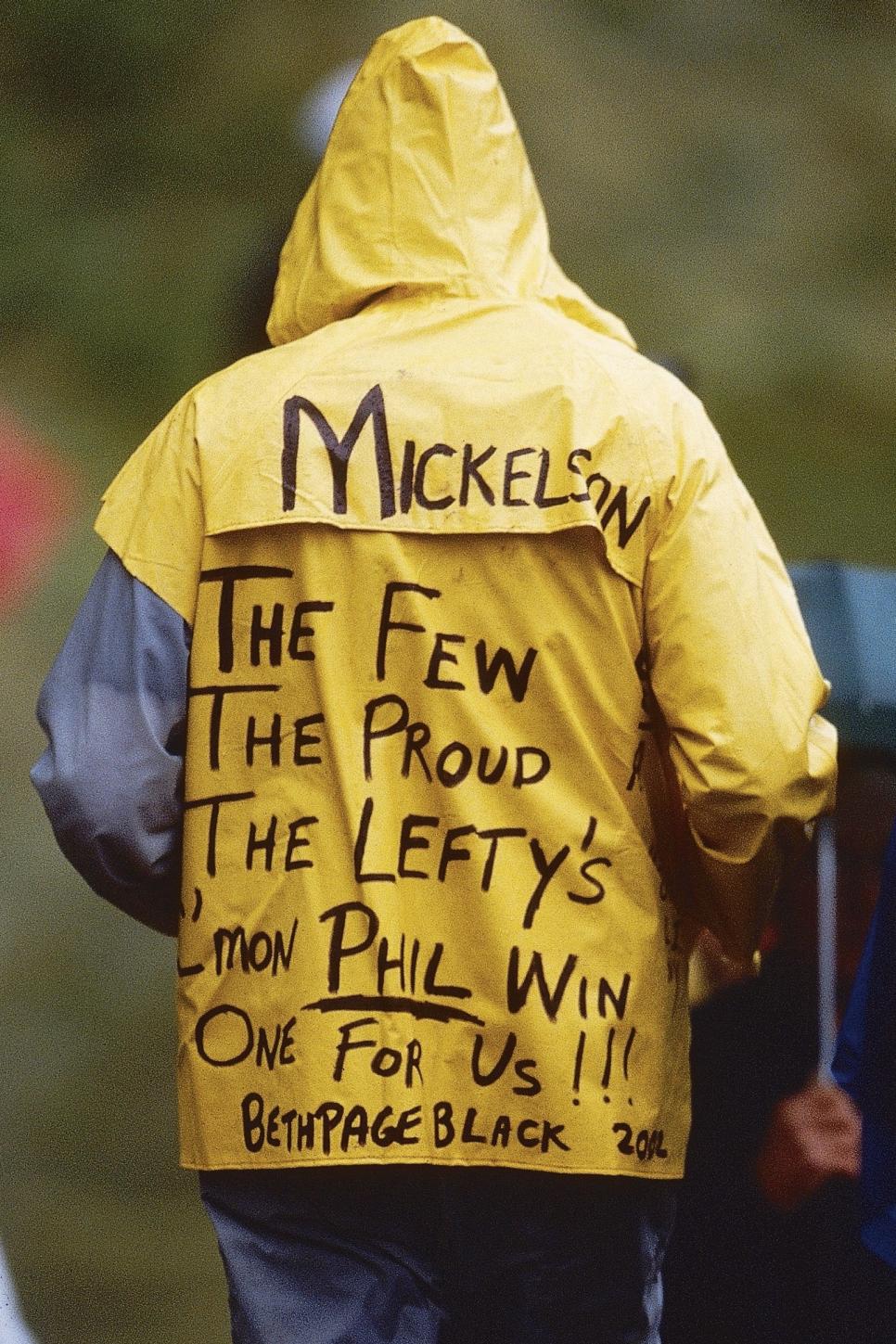

All along the way he signed every autograph and tipped big, leading cynics to wonder if it was all fake. Maybe, but in 2002 at the so-called People’s U.S. Open at Bethpage, the New York fans, with their acute radar for phony, adopted Mickelson as the “people’s champion.” Mickelson had come to be regarded as one of the players who, no matter how he played, was good for golf.

Al Tielemans

At that point in his career, the only thing about Mickelson that nettled the public was a propensity to fall short on the game’s biggest stages, which changed at the 2004 Masters, where when the Californian broke an 0-for-46 career tally in major championships with a dramatic victory. Twenty years later, however, that narrative has flipped. Mickelson has six major wins among his 45 victories and in the opinion of many is a top-10 all-time player. But fans have increasingly found him not only tougher to love, but to understand. And Mickelson is a pariah to much of the golf establishment that once embraced him.